1811 quakes were "36,000 times" more powerful than Wednesday's event

Residents very close to Williamsville may have felt the ground shake a second time Wednesday night, but the force of the magnitude 2.5 aftershock was 50 times less than the main quake, according to researchers with the University of Memphis.

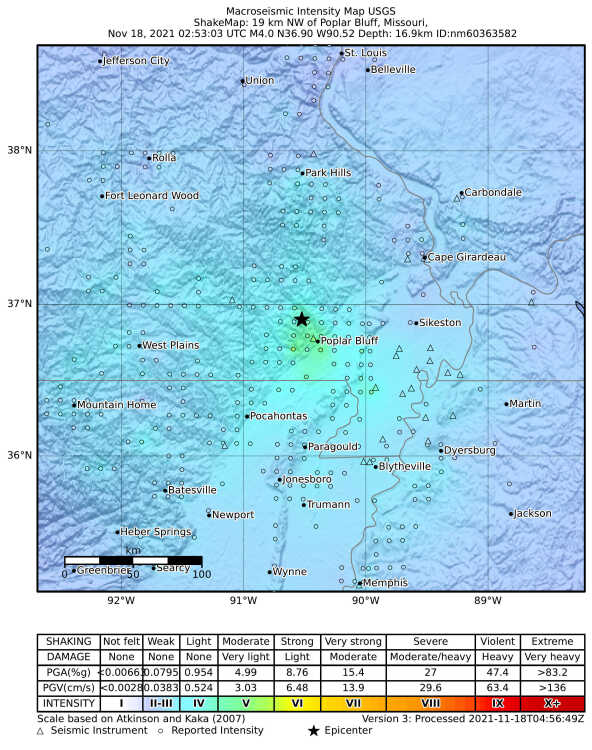

A magnitude 4.0 earthquake was widely felt across Missouri, Arkansas and other parts of the region at 8:53 p.m. Wednesday, briefly alarming many residents who were confused by the rare larger quake.

The Nov. 17 event marks the region’s ninth-largest earthquake in the past 50 years. It was centered five miles south, southeast of Williamsville, according to the U.S. Geological Survey and had a depth of 10.5 miles.

The aftershock hit at about 9:40 p.m., with a depth of about 10 miles. Its epicenter was slightly south and west of the original quake.

The region actually has about 200 small tremblors per year, explained Mitch Withers, who has been with the Center for Earthquake Research and Information for the past 24 years. CERI operates out of the University of Memphis and continues to study the unusual New Madrid Seismic Zone.

“Most of those earthquakes are in the magnitude 2.0 range, so they’re pretty small,” Withers said. “Most people won’t feel them.

“Poplar Bluff is a little bit outside that active part of the New Madrid Seismic Zone, so it’s a little more unusual where this earthquake was, but it does have a history of seismicity and it’s related.”

The largest quake on that top 10 list for recent years was a magnitude 4.7 that was centered near Chaffee about 31 years ago. Seismometers have measured the shaking in Southeast Missouri since about 1974, the USGS reports.

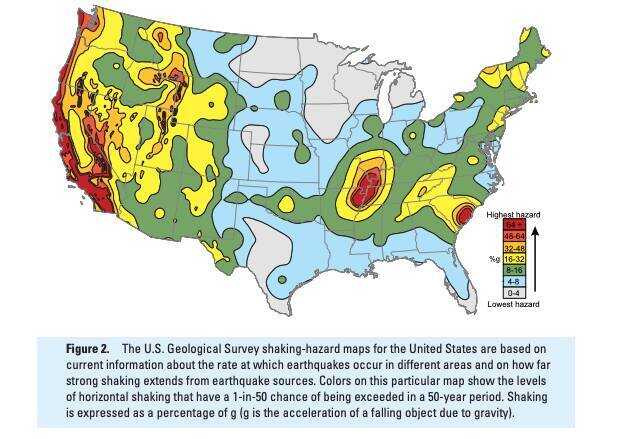

Scientists have yet to figure out the cause for the NMSZ’s quakes, Withers said Thursday, but they have gained a greater understanding of why the force of the quakes is felt at a much larger distance than those in areas such as California.

1811 quakes 36,000 times more powerful than 4.0

A series of large quakes in 1811 were felt over 2 million square miles, for example.

Those magnitude 7.5 to 8.2 quakes were 36,000 times more powerful than Wednesday’s 4.0, Withers said. The power of a quake increases exponentially as it moves over the magnitude scale, which measures the maximum motion recorded by a seismograph.

Earthquakes typically occur along the boundaries of the seven major tectonic plates that make up the planet’s crust, but the NMSZ is thousands of miles from the nearest plate boundary, in an area scientists would normally consider stable.

“There’s an ancient, failed rift and it creates a geologic structure on which this earthquake occurred,” Withers said.

Scientists believe that during the process of continental rifting — a time about 600 million years ago when the North American continent almost broke apart — a deep valley formed that is bordered by faults and is known as the Reelfoot Rift.

“There are some theories out there but we still don’t really know for sure why we have earthquakes in New Madrid and not say up in Chicago,” Withers said. “We haven’t gotten that big breakthrough yet. But we now know more than we did before, especially with what kind of impacts a larger earthquake might have had. That is where the big strides and knowledge have improved.”

The 1811 series of quakes were the largest in the history of the continental U.S. It is believed the NMSZ has seen large quakes like that in 1450 A.D., 900 A.D., 300 A.D. and 2350 B.C.

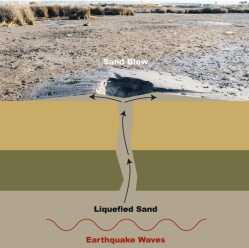

This knowledge was gathered by archaeologists who studied soil, and a specific occurrence, liquefaction. This occurs when tremendous shaking forces an eruption of water and sand to the ground surface, known as sand blows.

Dating when these have occurred has helped paleoseismologists learn more about the NMSZ, particularly in the last decade, according to the USGS.

Felt distance 3x greater

The “felt” distance is greater when the NMSZ shakes because the area has “old and cold rocks,” Withers explained.

“An equivalent magnitude earthquake in California ... The waves will die down with the distance traveled. The rocks in California, it’s very geographically active. The rocks out there are hotter (temperature) and fractured a lot more because it’s an active boundary.”

The Central U.S. is considered stable, and hasn’t had any active geology in millions of years.

“It’s kind of like the difference between a bell ringing and a cracked bell ringing. The cracked bell doesn’t ring nearly as well as the competent bell,” Withers said.

As an example, a magnitude 5.8 earthquake in Virginia was felt up to 600 miles from the epicenter in 2011. A magnitude 6.0 quake — which released twice as much energy — was only felt about 250 miles from its epicenter.

Low chance of ‘big one’

Withers said while Wednesday’s quake was larger than normal, it shouldn’t be seen an indication of something larger to come.

“The statistics are relatively stable,” he said. “What concerns me the most is not the big 1811 earthquake. That’s a relatively low probability on the order of 10-20%.

“It’s the magnitude 6’s, like Virginia, that can do some damage. That’s probably on the order of 40-60% ... in the next 50 years, in the entire central U.S.”

It’s a large margin because researchers just don’t have enough knowledge to be too accurate with that, Withers said.

Damage to structures does not typically occur until a quake is a magnitude 5.5 or higher.